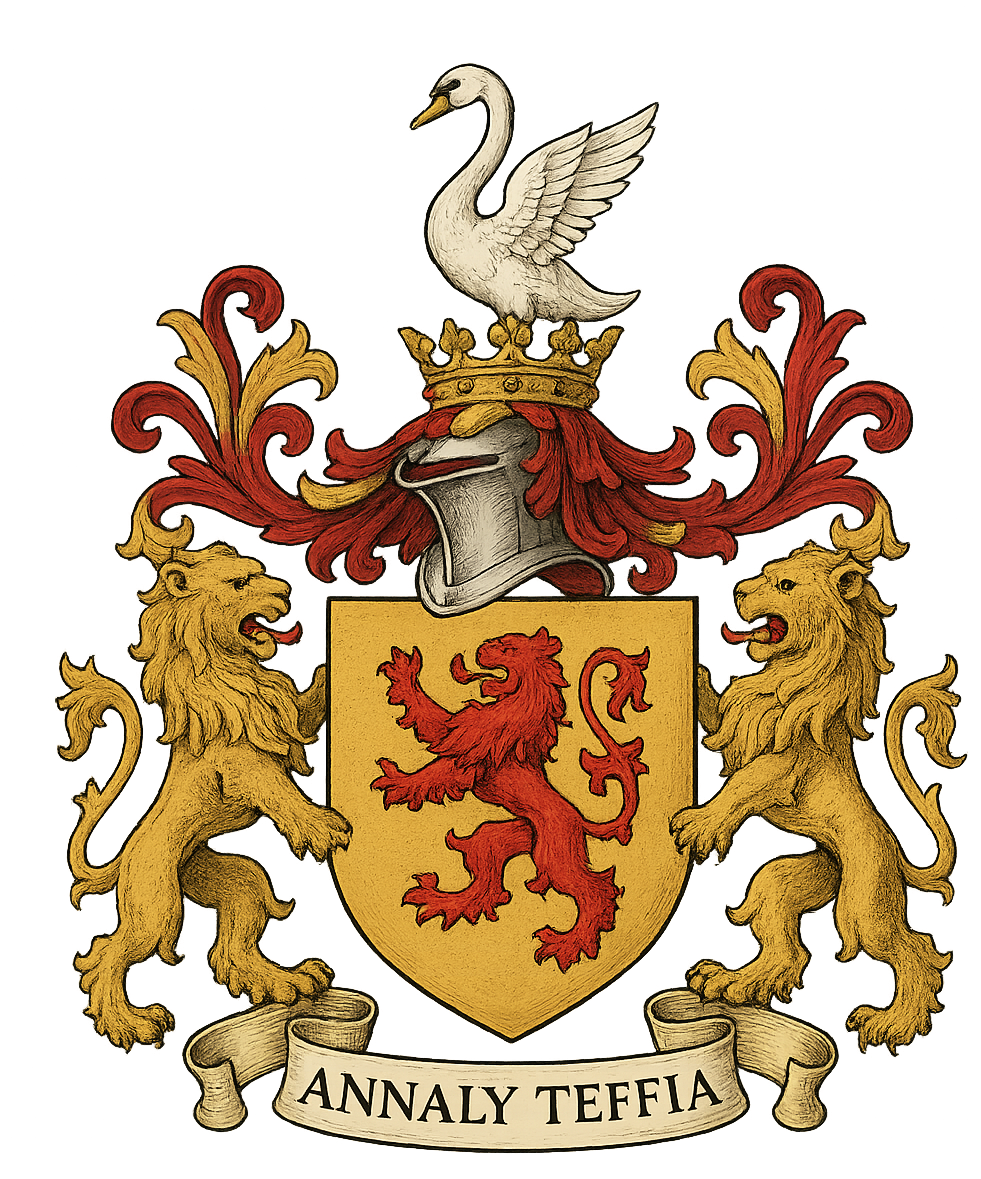

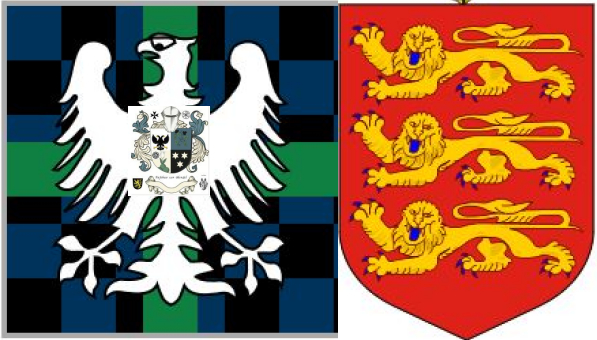

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

**Irish Property Rights and Feudal Grants:The Seignory, Barony, and Honour of Longford** The history of Irish property rights is inseparable from the transformation of Gaelic lordship into English-style feudal tenure. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in the evolution of the Seignory, Barony, and Honour of Longford, historically known as Annaly or Anghaile, the ancient principality of the Ó Fearghail (O’Farrell) dynasty. The Honour and Seignory of Longford represent a rare legal and historical structure in which Gaelic kingship, monastic authority, Norman barony, and Crown feudalism intersected over the course of nearly nine centuries. The result is one of the most complex and interesting property-rights successions in all of Ireland. I. Gaelic Foundations: Property as a Fusion of Territory and Sacred AuthorityBefore the arrival of the Normans, Irish property rights operated under Brehon Law, a sophisticated system where land was:

In Annaly, the various lords and princes ruled the sovereign territory not only through force but through spiritual patronage of sacred sites such as Ardagh, Inchcleraun, and numerous monastic islands on Lough Ree. Gaelic lordship integrated temporal power with ecclesiastical legitimacy; property was not merely land, but a network of sacred places, burial grounds, abbey lands, tithes, and clan territories. Thus, when the English Crown later created feudal grants, it needed to recreate both the temporal and spiritual infrastructure of sovereignty. This would become crucial in the formation of the Honour and Seignory of Longford. II. Norman and Crown Intervention: Converting Gaelic Territories into Feudal PropertyWith the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the 12th century—led by Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath—the Crown sought to replace Gaelic sovereign units with feudal property units. The Normans introduced feudal concepts such as:

The Lordship of Meath itself was a palatine lordship, meaning it exercised near-royal authority independent of the King. Annaly, lying on its western marches, became part of this structure when various grants were made to the de Nogent/Nugent family, the Barons Delvin. These Norman grants did not erase Gaelic structures; they superimposed feudal law onto Gaelic territory, creating hybrid rights that later became legally significant. III. Tudor and Stuart Patents: The Legal Creation of the Seignory and Honour of LongfordThe most important transformation occurred during the 16th and early 17th centuries, when the Tudor and Stuart monarchs issued a series of royal patents that legally restructured Annaly under English law. Key grants from:

granted the Barons Delvin: 1. Manors, castles, and lands of Annalyincluding Granard, Lissardowlan, and O’Farrell-controlled estates. 2. Markets, fairs, courts, and judicial rightssuch as Court Baron and Court Leet, the backbone of medieval territorial governance. 3. Captaincy and Chiefship of Slewght WilliamElizabeth I’s 1565 grant effectively transferred the political role of the O’Farrell prince to the Nugent Baron Delvin, making him “Chief of the Country” with hereditary military and civil authority. 4. Fishing, foreshore, and water rightsincluding eel weirs, salmon rights, riverbanks, lake islands, and Lough Ree navigational privileges. 5. Ecclesiastical patronageadvowsons, tithes, abbey lands, and rights over monastic islands, formerly held by O’Farrell princes and pre-Norman monasteries. 6. Islands of Lough Reeincluding Inchcleraun, Inchmore, and others—critical sacred and economic centers. Collectively, these grants formed the Honour and Seignory of Longford, a feudal dignity that replaced the Gaelic principality with a Crown-created territorial authority. An Honour was more than a landholding—it was a jurisdiction. In medieval English law, the holder of an Honour controlled courts, services, rents, and territorial rights akin to a small autonomous polity. Longford’s Honour was thus the Crown’s legal framework for transferring the full sovereignty of Annaly to the Nugent lineage. IV. Property Rights in the Honour: What the Seignory Legally ContainedUnder feudal law, an Honour or Seignory included: A. Territorial Rights

B. Jurisdictional Rights

C. Economic Rights

D. Water Rights

E. Ecclesiastical Rights

The total package of rights made the Honour of Longford functionally equivalent to a territorial lordship or semi-principality under English law. V. Dissolution, Survival, and Modern Position of These RightsIreland’s property law evolved dramatically with:

However: Feudal tenures were abolished, but feudal dignities were not.Under modern Irish law:

Thus, the Seignory / Honour of Longford, if registered, continues today as:

It carries no modern governmental power, but its historical rights, origins, and legal foundation remain intact. VI. The Significance in Irish Legal HistoryThe Honour and Seignory of Longford demonstrate:

Few Irish lordships encapsulate such a complete legal transformation. ConclusionThe Seignory, Barony, and Honour of Longford represent a remarkable continuity of Irish property rights, moving from:

These grants preserved not only the land but the spiritual, judicial, and economic rights that once defined the sovereignty of the O’Farrell princes. In their later form, such rights were transferred to the Barons Delvin and Earls of Westmeath, forming an Honour that remains one of Ireland’s most historically significant feudal dignities. IRISH LAW TODAYIn modern Ireland:

If the Honour & Seignory of Annaly was conveyed (as it appears in 1996), then any non-territorial, incorporeal rights would follow the Honour. However:Actual ownership of foreshore/fishing rights would depend on:

Rights likely to persist as incorporeal hereditaments:✔ titular fisheries Rights NOT likely to persist today:❌ exclusive fishery rights But historically? VI. FINAL CONCLUSIONYes—the Baron Delvin, as feudal lord and later Earl of Westmeath, held significant historical rights to foreshore, fishing, waterways, islands, and riparian governance in Annaly (modern County Longford), based on: ✔ explicit Tudor/Stuart patents✔ the Captaincy of Slewght William✔ rights to abbeys and monastic fisheries✔ island and lake grants✔ broad feudal language (“all rights, privileges, liberties, perquisites”)✔ his role as successor to the O’Farrell princes✔ his position within the Palatine Lordship of MeathThese rights formed part of the Honour & Seignory of Annaly and were historically meaningful, economically valuable, and central to the governance of the principality’s river-and-lake driven economy. Character of the interestThe Honour and Seignory of Annaly (Teffia), historically associated with the region later corresponding broadly to County Longford, is properly described in modern Irish law as an incorporeal hereditament, that is, a heritable real right of an intangible nature rather than an estate in the corporeal soil. As such, it consists in a complex of dignitary and seignorial rights (including styles of honour, ceremonial jurisdiction and historic franchises) held in gross and not as a present estate in land. As an incorporeal hereditament, the interest falls within the category of real property capable of ownership, inheritance and conveyance, analogous in legal structure (though not in content) to other incorporeal rights such as easements, profits or rights of way, but distinguished by its essentially dignitary and jurisdictional character. It is therefore dealt with in conveyancing as an item of intangible realty, rather than as a mere personal honour or status. Historical derivation and conveyanceThe seignorial complex associated with Annaly–Longford arose out of medieval grants within the Anglo‑Norman lordship, superimposed upon earlier Gaelic princely structures in the midlands, with later confirmations and re‑grants under the Crown embedding it within the Anglo‑Irish feudal and statutory framework. By the early modern period, these rights had become appurtenant to the Nugent family as Barons Delvin and later Earls of Westmeath, in whom the seignory and associated honours of Longford and Annaly were consolidated. In the late twentieth and early twenty‑first centuries, the surviving feudal and dignitary components were the subject of inter vivos conveyances in fee simple, whereby the Earl of Westmeath conveyed his remaining rights of honour, barony and seignory of Longford (including the Annaly complex) to Dr George Mentz, Seigneur of Blondel, with language purporting to pass “all rights, privileges and perquisites” of the barony and seignory. These instruments treat the interest expressly as heritable incorporeal property capable of absolute ownership and transfer, rather than as a mere personal or familial distinction. Position within Irish incorporeal hereditamentsIrish land registration rules recognise that incorporeal hereditaments “held in gross” (that is, not merely appurtenant to a particular dominant tenement) may be the subject of registration with absolute or possessory title, where the derivation of both grantor’s and grantee’s estates is satisfactorily established. In that framework, a feudal honour or seignory such as Annaly–Longford is treated as a discrete registrable real right, separate from any present freehold in land but transmissible and enforceable as property. Manorial and feudal dignities in the British and Irish context are generally classified in practice as incorporeal hereditaments: they are incapable of physical possession, but they are recognised as inheritable property rights, comparable in legal category (though not in function) to manorial lordships, prescriptive baronies, coats of arms and hereditary offices. While their historic incidenta might have included markets, fairs and courts, in contemporary law their surviving content is overwhelmingly ceremonial and dignitary, and they do not confer any public or governmental authority. Nature and limits of the principality styleThe designation of Annaly as a “principality” reflects its historic status as a territorial and princely jurisdiction under both Gaelic and feudal arrangements, but in modern Irish law this style is understood as part of the dignity attaching to the incorporeal hereditament rather than as a claim to sovereignty. The present interest is thus a private law right: it may carry titles, precedence and ceremonial privileges, and may be bought, sold or inherited as property, but it does not displace the constitutional authority of the State or create any parallel system of public governance. Valuation of such interests for private transactions focuses on their historic provenance, documentary continuity, recognition within specialist markets for feudal and manorial dignities, and any surviving ceremonial or associative privileges, rather than on yield from land or public jurisdiction. Within Irish incorporeal property, Annaly–Longford therefore exemplifies the survival of a medieval feudal complex as a modern, transferable, incorporeal hereditament in real property law.

The Earl of Westmeath’s claimed succession rests on a combination of historical Crown grants, territorial aggregation under the Nugents, and modern treatment of such dignities as inheritable incorporeal property rather than mere courtesy styles. Historical Crown grants and aggregation

From Gaelic principalities to Nugent dignities

Incorporeal hereditament theory and princely succession

Why the Earl of Westmeath in particular

In short, the claim is that the Earl of Westmeath is successor not to territorial sovereignty but to a bundle of feudal and princely dignities, recognised in modern private law as incorporeal hereditaments derived from medieval Crown and Gaelic structures.

WHAT RIGHTS SURVIVE TODAY AS INCORPOREAL HEREDITAMENTSThese are the rights that survived the Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act 2009 IF they were properly registered in the Registry of Deeds prior to abolition. They include the following categories: 1. Feudal Dignities and HonoursThese are hereditary titles of dignity, not peerages, and still fully legal to own and transfer: ✔ Seignory / Seigneurial Rights✔ Feudal Baronies✔ Honours (large composite feudal jurisdictions)✔ Lordships of Manors (in name/title)✔ Styles, titles, and dignitary precedence associated with the honourThese titles carry no modern political power, but they remain real hereditary property rights. 2. Certain Historical Manorial Rights (Non-Territorial)These are rights that do not require owning land yet were part of the lordship itself: ✔ Right to hold or claim the Manorial Title(e.g., Lord of Annaly, Baron of Longford, Seigneur of X) ✔ Right to armorial bearings associated with the honour(if historically documented) ✔ Right to ceremonial manorial courtsNot enforceable as judicial bodies, but the right to convene them survives symbolically. ✔ Right to certain traditional feudal incidents—provided they do not involve land ownership today. Examples include:

These rights are largely ceremonial but legally real property interests. 3. Rights Attached to Ancient Jurisdictions (Now Symbolic)Feudal honours often had:

Modern Ireland abolished their exercise, but the right to the title of the court or jurisdiction survives as a heritage dignity: ✔ “Lord of the Court Leet of Longford”✔ “Lord of the Manor with ancient Market Rights”✔ “Holder of the Honour and Seignory of Annaly”These cannot be exercised, but the right to the dignity remains a property interest. 4. Embodied Historical Rights (Symbolic but Transferable)Some incorporeal hereditaments consist of historical relationships and identities, such as: ✔ Stewardships, Bailiwicks, and specific feudal offices(e.g., “Bailiff of Annaly,” “Constable of X,” “Keeper of Y Island,” etc.) ✔ Rights of representation in heritage and ceremonial contexts✔ Right to the historical narrative, coat of dignity, and succession chainFor example:

This is legally meaningful in the same way Scottish barons and English manorial lords are recognized today. 5. Certain Profits à Prendre (IF Explicitly Registered)In rare cases, old incorporeal property rights may survive if they were never extinguished and were registered: ✔ Turbary rights (cutting turf/peat)✔ Grazing rights✔ Common pasture rights✔ Right of way / easementsThese only survive if:

These are uncommon but legally possible. 6. Ecclesiastical or Monastic Patronage Rights (Usually Symbolic)If named in the historical grants and registered: ✔ Advowsons (rights of church patronage)No longer exercisable due to church reforms, ✔ Titles associated with dissolved abbeys or monastic islandsE.g., “Lord of Inchcleraun,” “Keeper of St. Diarmaid’s Island.” These exist as incorporeal heritage dignities—not religious authority. SUMMARY TABLE — SURVIVING RIGHTS

FINAL ANSWERIf the Seignory, Barony, and Honour of Longford were properly registered in the Registry of Deeds, the modern holder legally possesses: **✔ A real, inheritable, transferable property right✔ Known as an incorporeal hereditament This means the holder is the legal successor-in-title to the ancient Honour—but not the ruler of the land. It is the same legal category as:

All are recognized property, even though they no longer carry territorial authority. **Manorial Property Rights and Incorporeal Hereditaments(A Complete Legal Analysis)** Manorial rights are a special class of incorporeal hereditaments, meaning intangible property rights that can exist independently of land ownership. Many of these rights—if properly recorded—survived the abolition of feudal tenure and remain enforceable or, at minimum, legally recognized as dignities or property interests. Below is a breakdown of each category. 1. MANORIAL WASTEDefinitionManorial waste refers to unoccupied, uncultivated, or common areas within the lordship that historically belonged to the Lord of the Manor. Examples include:

Rights IncludedThe Lord formerly had:

Modern StatusManorial waste as land generally no longer exists in Ireland after 2009 unless separately registered as

freehold. 2. MANORIAL COMMONDefinitionManorial commons were lands over which the tenants held rights of common, such as grazing or turbary, while the Lord owned the soil. Rights commonly included:

Rights of the LordThe Lord retained:

Modern SurvivalCommons rights still exist if not extinguished. 3. MANORIAL INCIDENCEManorial incidences were obligations owed by tenants to the Lord. Historically, these included: A. Quit Rents and Chief RentsAnnual payments for holding land. B. HeriotsA death-duty (best beast or value thereof). Rare in Ireland but existed. C. Suit of CourtThe obligation to attend the Lord’s Court Baron or Court Leet. D. ReliefA payment upon inheritance of a tenancy. E. Fines for alienationFees payable when a tenant sold or transferred his land. Modern StatusMost incidences tied to tenure were abolished, but the right to the manorial titles, courts, and dignities remains an incorporeal hereditament. 4. WATER RIGHTS (RIPARIAN RIGHTS)Riparian (water-adjoining) rights historically attached to both the Lordship and to individual tenants. Lord’s Rights Included:

In Annaly/Longford:Because Lough Ree and the Shannon dominated the region, the Barons Delvin held extensive water-related privileges, often explicitly granted (“all waters, watercourses and islands belonging…”). Modern StatusRiparian rights exist only if the Lord retained ownership of adjoining land. 5. FORESHORE RIGHTSDefinitionForeshore = land between the high-water and low-water marks. Normally owned by the Crown unless granted away. Lord’s Historical RightsIf granted by Crown patent (as in Lough Ree patents):

Status in AnnalyTudor grants often conveyed:

Modern StatusExclusive foreshore ownership usually ends unless explicitly preserved. 6. FISHING RIGHTS (PISCARY RIGHTS)Three Types:A. Several Fishery (Exclusive)Full private fishery owned by the Lord. B. Free FisheryA Crown-created exclusive right. C. Common of PiscaryShared fishing rights among tenants. Rights Included:

Annaly ContextLough Ree’s islands were monastic fishing stations. Modern StatusOnly survive if separately registered or attached to freehold. 7. RIGHTS OF LIGHT (ANCIENT LIGHTS)DefinitionA property right that windows or openings receive unobstructed light. Though more common in urban manors, rural manors had:

SurvivalRights of light survive as easements only if tied to land. As a manorial dignity? Survives symbolically. 8. USUFRUCTS & SERVITUDESUsufructThe right to use and enjoy the products of land without owning the land. Typical manorial usufructs:

ServitudesRights over another’s land:

These were integral to manorialism. Modern StatusThey survive if registered or expressly preserved—otherwise extinguished. The title to historic servitudes remains part of the Honour’s dignity. 9. OTHER MANORIAL HEREDITAMENTSA. Rights to Hold CourtsCourt Baron and Court Leet. B. Rights to Appoint Officers

These are now symbolic but historically part of the Honour. C. Rights to hold fairs and marketsThough markets are regulated today, the dignity remains. D. Rights to treasure trove (historically)If found on manorial lands, part belonged to the Lord. E. Rights to mines, minerals, or quarriesOnly if not severed by Crown or statute. FINAL SUMMARY — WHAT THESE RIGHTS MEAN TODAYThese rights no longer grant political or territorial power, but they remain real property when classed as incorporeal hereditaments, which include: ✔ the manorial title✔ the dignity attached to the Honour or Seignory✔ the ceremonial identities of courts, offices, and privileges✔ symbolic rights to commons, waste, water, and fisheries✔ residual or historical easements and servitudes✔ any freehold or specific rights separately registeredThey are inheritable, transferable, registrable, and legally recognized as non-territorial property interests. For the Honour & Seignory of Longford (Annaly), this means: The modern holder retains the historic dignity and symbolic rights of the feudal lordship, even though the land-based powers have faded.The Honour survives as a prestigious, legally valid, incorporeal hereditament rooted in centuries of Irish property law. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

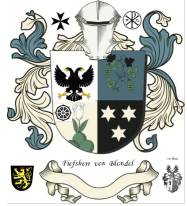

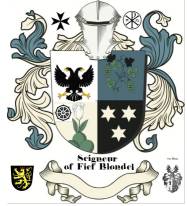

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News