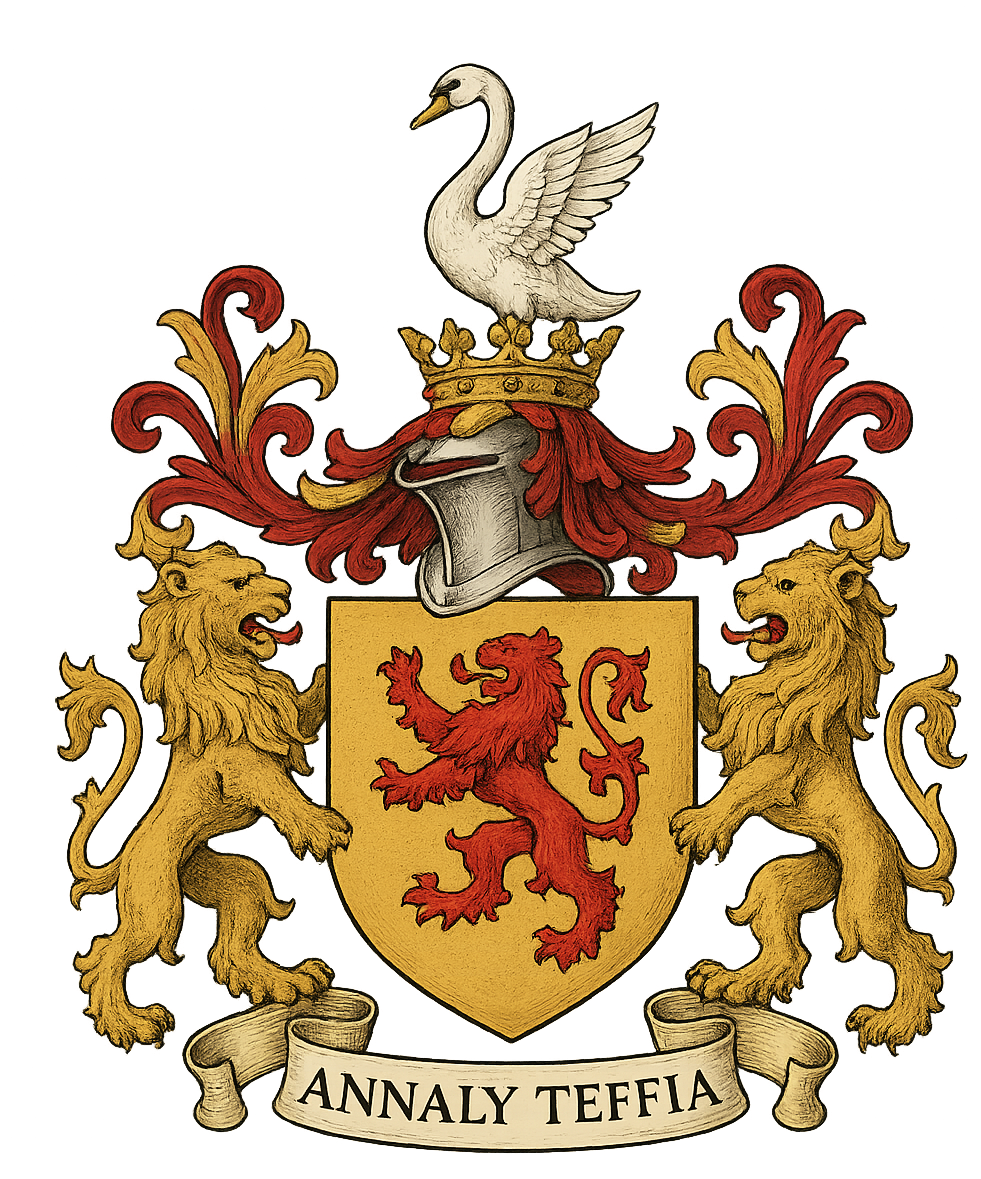

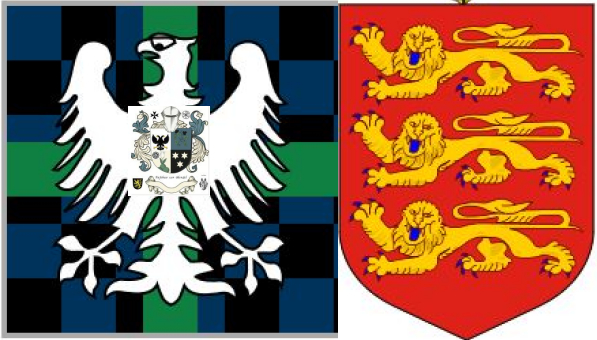

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

The Transfer of the Caput of Tír Uí Chuinn Kingdom of Rathline and CashellHow the English Crown Replaced a Gaelic Kingdom with the Baron of DelvinThe grant dates to the 28th regnal year of Queen Elizabeth I — that is, 1586.

IntroductionIn the later sixteenth century, the Crown of England pursued a deliberate policy in Ireland: not merely the conquest of land, but the replacement of indigenous kingship with loyal baronial authority. This was achieved not by openly recognizing or recreating Gaelic kingdoms, but by dismantling their spiritual and economic foundations and transferring those foundations to trusted Anglo-Irish magnates. Nowhere is this policy clearer than in the Crown grant commonly catalogued as LV.–27 in the Calendar of Patent Rolls, by which the King’s authority vested the spiritual, temporal, and symbolic seat (caput) of Rathline and Cashell—the historic center of the O’Quin polity—in the Baron of Delvin and his heirs. Rathline and Cashell as a Gaelic Royal SeatRathline was not a mere parish. It functioned historically as the royal seat of the O’Quin (Uí Chuinn), where kingship was expressed through:

In Gaelic Ireland, temporal authority and spiritual legitimacy were inseparable. The king ruled not only through arms, but through church patronage, ecclesiastical revenues, and the control of the royal–sacred seat. The Crown understood this system well—and dismantled it with precision. The Tudor Legal Mechanism of SupplantationRather than granting “the kingdom” of Rathline—language that would acknowledge Gaelic sovereignty—the Crown used a more effective instrument: property law combined with ecclesiastical transfer. Under the reign of Elizabeth I, the Crown issued a patent to Mary, Lady Delvin, and her son Richard Nugent, granting:

This was not accidental drafting. It was intentional replacement. Transfer of the Spiritual CaputThe grant conveyed the entire ecclesiastical apparatus of Rathline and Cashell:

This made the Baron of Delvin the lay impropriator and spiritual patron of the parishes. In Gaelic political culture, the authority to control the church at the royal seat was one of the defining attributes of kingship. By transferring these rights, the Crown removed the O’Quin from spiritual legitimacy and vested it in Delvin. Transfer of the Temporal and Symbolic SeatAlthough the patent does not expressly name “the castle of Rathline,” it grants:

In Tudor legal usage, “site and buildings” included standing and ruined structures, including former fortifications absorbed into ecclesiastical precincts. This language was routinely used to transfer former Gaelic royal seats without naming them as such—a deliberate refusal to acknowledge dynastic continuity. Thus, the Baron of Delvin received the physical and symbolic caput of the former kingdom: the place from which authority had historically radiated. Hereditaments and Inheritable AuthorityThe use of the word “hereditaments” is decisive. In English and Irish common law, hereditaments comprised all inheritable rights capable of descent, both corporeal and incorporeal. By granting the hereditaments of Rathline and Cashell, the Crown ensured that:

passed to Delvin and his heirs, not merely for life, but as a permanent dynastic settlement. This transformed Delvin from a landholder into the successor authority at the ancient seat, albeit now under Crown sovereignty. Supplantation Without RecognitionThe brilliance—and ruthlessness—of Tudor policy lies here:

Yet in practice:

What was removed in law was recreated in function—under a loyal baron. England, Scotland, and the Crown’s ContinuityAt the time of the grant, the authority flowed from the English Crown ruling Ireland. With the later Union of the Crowns under James VI of Scotland and I of England, this settlement stood confirmed under a single British monarchy, ensuring continuity of Delvin’s rights and inheritance. Thus, the transfer was not temporary or experimental; it was a permanent re-ordering of authority, carried forward into the British constitutional framework. ConclusionThe Crown’s grant to the Baron of Delvin did not merely convey land. It conveyed:

In this way, the King of England—acting through Tudor law—supplanted a Gaelic kingship without naming it, and installed a new lord at its ancient seat. The old kingdom was erased in language, but replaced in fact. This pattern—replacement through ecclesiastical and proprietary transfer rather than overt conquest—defines the Tudor transformation of Ireland, and Rathline stands as one of its clearest examples. King James did reconfirm Rathline and Cashell as part of the Delvin/Nugent settlement, but he did so by confirmation and continuation, not by creating a new grant or restyling the territory as a kingdom or liberty. Below is the precise, historically accurate explanation. 1. Which “King James” and WhenThe reconfirmation would have been under:

This matters because James’s Irish policy explicitly relied on reconfirming Tudor grants to stabilize authority after Elizabeth I’s reign. 2. What James I Actually Reconfirmed (Very Important Distinction)James I did not issue a fresh “grant of Rathline and Cashell” in the sense of a new conveyance. Instead, he followed a standard post-1603 practice: He confirmed and continued:

This typically appeared as:

So Rathline and Cashell were reconfirmed as already held, not re-created. 3. Why James I Reconfirmed These HoldingsJames’s Irish strategy rested on three pillars:

Rathline and Cashell fit this policy perfectly. 4. What the Reconfirmation Covered (Functionally)James’s confirmation would have embraced:

In other words:

|

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News